Who was Eve Leary? The name haunts modern Georgetown, attached to police headquarters and military barracks, yet its origins dissolve into the humid mists of colonial memory. In truth, Eve Leary was less a person than a palimpsest—the name given to a Demerara plantation that bore witness to the extraordinary life of Sara Thibou (1711-1780s), a Huguenot descendant whose family fled the midnight cellars of religious persecution in France only to become architects of a different oppression in the Caribbean.

Sara’s story unfolds across three marriages—first to Joseph Matthews, who taught her the brutal mathematics of sugar and slavery; then to the tyrannical Cornelis Leary, whose name would mysteriously attach itself to their plantation; and finally to Jacob Bogman, the Dutch surveyor who had mapped Maroon settlements and named one “Bogman’s Glory” with characteristic hubris. Through widowhood, legal battles with her own children, and the relentless transformations of empire—Dutch to British, sugar to cotton, slavery toward its eventual abolition—Sara Thibou carved out autonomy in a world designed to deny it to women, all while perpetuating the very system of bondage her ancestors had fled.

Her grandson, Joseph Thibou Matthews, writing his doctoral thesis in Amsterdam in 1801, would struggle to reconcile his grandmother’s fierce survival with his enlightenment ideals, understanding that she had been both victim and perpetrator, shaped by forces of persecution and profit that transformed human beings into property and property into legacy. The Eve Leary estate stands today as a monument to these contradictions—a name whose origins are forgotten, marking a place where French psalms sung in secret gave way to the songs of enslaved Africans, where religious refugees became enslavers, where a woman’s battle for autonomy was built on others’ bondage, and where the machinery of empire ground on, indifferent to the small tragedies and triumphs of those caught in its gears.

Huguenot Upbringing

The candlelit cellars of Lyon still haunted Sara’s dreams, even here in the blazing Caribbean sun. Her grandmother Marie would speak of them in hushed tones—how the Huguenots had gathered in secret, their Calvinist prayers whispered like sedition while Catholic authorities prowled the streets above. “We sang the Psalms in darkness,” Marie had told her, aged fingers tracing invisible patterns of faith, “each word an act of defiance, each breath a risk of the galleys or the stake.”

That inheritance of persecution had shaped the Thibou family like a smith shapes iron—through fire, pressure, and relentless hammering. When Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, the Thibous joined the great exodus, their faith driving them across an ocean to uncertainties that seemed preferable to the certainties of religious oppression. First to the Carolinas, where they tried to root themselves in that alien soil, then to Antigua, following the promise of sugar wealth and Protestant tolerance.

Sara Thibou and Joseph Matthews

Standing in her father’s house in Antigua, St. John’s Parish on the morning of April 2nd, 1728, Sara Thibou understood that she was about to enter into more than just marriage with Joseph Matthews. She was stepping into the machinery of empire—a system as complex and brutal as the Inquisition, her family had fled, but she was dressed in different clothes and speaking different justifications.

The wedding itself was a careful choreography of colonial society. Anglican prayers mingled with the French accents of Huguenot refugees. At the same time, outside the church, enslaved Africans laboured under the Caribbean sun to produce the very sugar that sweetened the wedding feast. The irony was not lost on Sara—her family had fled religious bondage only to prosper through the physical bondage of others.

“The colonies exist,” her father had explained years before, “because Europe hungers for what it cannot produce. Sugar, coffee, and indigo are the new sacraments of commerce.” Jacob Thibou, survivor of persecution, had learned to speak the language of profit with the same fervour his ancestors had reserved for scripture.

Joseph Matthews proved himself a patient teacher in the arts of colonial survival. Their plantation in Antigua operated according to its own brutal mathematics—so many enslaved workers per acre, so many pounds of sugar per worker, so many deaths per harvest factored into the cost of doing business. Sara learned these calculations with the same discipline her grandmother had applied to memorising psalms in secret.

“The French control Martinique and Guadeloupe,” Joseph explained one evening, spreading maps across their dining table. “The Spanish hold the mainland from the Orinoco to New Spain. The Dutch have Essequibo and Berbice, the English Jamaica and Barbados. Each power grasps for advantage, but the real war is fought in the price of sugar on the London exchange.”

Demerara and Essequibo

By 1740, when they decided to relocate to Demerara, Sara had borne six children and buried one. The promise of virgin land in the Dutch colonies represented not just opportunity but escape—from Antigua’s depleted soils, from the established hierarchies that limited advancement, from the ghosts of the child they’d lost to fever.

The voyage to Essequibo revealed the hidden networks of empire. Their ship stopped at Sint Eustatius, that free port where Dutch merchants traded with anyone with gold, regardless of flag or faith. French ships anchored beside English ones, Spanish silver flowed into Dutch coffers, and enslaved Africans were sold with the same casual efficiency as barrels of molasses.

The Dutch factor explained with mercantile pride that neutrality “is the most profitable position in any war.”

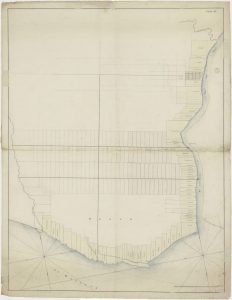

In 1740, Demerara was a frontier where European ambitions collided with American realities. The Dutch had established their claim through the West India Company, but their control extended barely beyond the river mouths. The jungle pressed in from all sides, thick with possibilities and dangers. Indigenous peoples—Arawak, Carib, Warao—moved through territories that European maps claimed but European power couldn’t truly command.

The First Plantation

Joseph threw himself into the work of plantation-building with almost religious fervour. Land had to be claimed from swamps and forests, ditches and canals dug to drain the coastal plains, and the agricultural infrastructure imposed upon a landscape that seemed actively hostile to European designs. Sara managed the household economy with equal intensity, negotiating with Dutch merchants, organising the enslaved workforce, and establishing the social connections to ensure survival in this new society.

The transformation of wilderness into profitable cultivation required more than just physical labor—it demanded a kind of willful blindness to the human cost. The enslaved workers who cleared the land, dug the canals, planted and harvested the sugar cane existed in colonial accounting as entries in a ledger, their humanity systematically erased by the demands of profit.

“We are building something permanent here,” Joseph would say, surveying their expanding domains. But Sara, remembering her grandmother’s stories of fleeing France, understood that permanence was always an illusion. Empires rose and fell like tides, leaving only the debris of human ambition in their wake.

The Death of Joseph

Joseph’s death in 1742 came during the rainy season, when the rivers ran high and brown with topsoil torn from the interior. The fever that took him was sudden but not uncommon—the colonies consumed European lives with almost the same casual indifference they showed toward enslaved Africans. Sara found herself alone with six children and a partially developed plantation, surrounded by creditors who smelled weakness like sharks smell blood.

Her salvation came through understanding the peculiar legal position of colonial widows. Dutch law, more liberal than English, allowed women to control property and conduct business. Sara weaponised her widowhood, playing the role of helpless female when it suited her while simultaneously orchestrating complex financial maneuvers that would have impressed the merchants of Amsterdam.

The marriage to Cornelis Leary in the mid-1740s was a calculated surrender to necessity. The Dutchman brought capital and connections; Sara brought land and legitimacy. That the marriage quickly soured into mutual antagonism surprised no one who knew Leary’s reputation. He was a man who confused brutality with strength, who ruled his plantation through fear while slowly destroying its value through mismanagement.

Women should know their place

“Your first husband was a fool to treat you as an equal,” Leary informed her with characteristic charm. “Women should know their place.”

Sara endured his tyranny with the same patience her Huguenot ancestors had shown toward Catholic persecution. She maintained her own networks, carefully documented his failures, and waited. The enslaved workers on the plantation, who bore the brunt of Leary’s cruelty, seemed to recognise in her a fellow sufferer under his regime. However, the gulf between their conditions remained unbridgeable. It is around this point that the plantation becomes known as “Leary’s Plantation” and ” Plantation de Leary”.

Leary’s death in 1772 freed Sara to face new battles. Her children, now grown into their own ambitions, viewed her as an obstacle to their inheritance. The court documents from this period reveal a family consumed by greed disguised as concern. When she announced her intention to marry Jacob Bogman—a surveyor and military man whose own history included charting Maroon settlements in Suriname, including the legendary “Bogman’s Glory”—her children’s opposition reached fever pitch.

The Court Battle

“She has been bewitched,” her son Jacob Jr. declared to the colonial court. “This Bogman seeks only her fortune.”

But Sara, at sixty, understood something her children didn’t: alliances were more valuable than autonomy in a colony where power shifted as rapidly as river channels. Bogman brought knowledge of the interior, connections to the Dutch military establishment, and most importantly, a pragmatic recognition of her value beyond her property.

Their marriage in 1773 was a contract between equals, each bringing assets the other required. Bogman needed social standing, and Sara needed protection from her children’s machinations. Together, they navigated the increasingly complex political landscape of Demerara as Dutch control weakened and British influence grew.

The 1780s brought new upheavals. The American Revolution disrupted trade patterns, the French entered the war against Britain, and the careful balance of Caribbean power shifted yet again. The French actually occupied Demerara briefly from 1782 to 1783, bringing with them revolutionary ideas that would eventually threaten the entire plantation system.

Sara watched these changes with the wisdom of age and experience. She had seen empires rise and fall, survived three husbands and outlived several children, and built and rebuilt her fortune through determination and calculated compromise. The plantation at Eve Leary had become a monument to endurance, its name persisting even as its ownership shifted through marriage, inheritance, and legal manipulation.

The Final Years

In her final years, arthritis gnarling the hands that had once signed marriage contracts and property deeds, Sara would sit by the Demerara River and contemplate the strange trajectories of history. Her Huguenot ancestors had fled France to preserve their faith; she had fled Antigua to protect her fortune. They had maintained their identity through secret worship; she had maintained hers through public litigation. The forms of survival changed, but the imperative remained constant.

The enslaved workers in her fields sang songs in languages she couldn’t understand, preserving their own histories of displacement and endurance. Sometimes, in their rhythms, she heard echoes of the Huguenot psalms sung in Lyon’s cellars—different words, different faiths, but the same human insistence on maintaining identity against systems designed to erase it.

When death finally came in the early 1780s, Sara Thibou Matthews Leary Bogman had outlived most of her contemporaries and illusions. The colonial records would remember her as a property owner, a litigant, a widow who married too often for propriety’s sake. But she knew herself as something more complex. This survivor had learned to use the very systems that constrained her. She was a woman who had carved out autonomy in a world that offered women few choices, a keeper of family memory who understood that persecution and complicity could coexist in the same person.

The Eve Leary Estate

The Eve Leary estate would outlive them all—through the transition from Dutch to British rule, the abolition of slavery, independence, and modernity. Its name would attach itself to military barracks and police headquarters, becoming a landmark whose origins grew ever more mysterious with time. But perhaps that was fitting for a place named by a woman who had spent her life negotiating the space between myth and reality, between the identities imposed by others and the ones she claimed for herself.

In Amsterdam, years after her death, her grandson Joseph Thibou Matthews would struggle to reconcile the grandmother he remembered with the historical figure he researched. His doctoral thesis at Leyden University examined concepts of natural law and human rights, ideas that starkly contradicted the system that had enriched his family. Yet he couldn’t dismiss Sara as simply another colonial oppressor. She had been shaped by forces larger than herself—by the religious persecution that drove her family from France, by the economic systems that made slavery profitable, by the gender constraints that limited her options.

Joseph Thibou Matthews

As Joseph wrote, the canals of Amsterdam reflected the winter sky, their surfaces holding perfect mirror images that shattered at the slightest disturbance. Truth, he was learning, was like that—clear until you tried to grasp it, fragmenting into countless perspectives the moment you disturbed its surface.

His grandmother’s story was part of a larger narrative—of Huguenots fleeing persecution only to become persecutors, of colonies built on noble ideals and brutal realities, of women navigating systems designed to exclude them, of names that outlive their origins and acquire new meanings with each generation. Eve Leary was all of this and none of it, a plantation that became a landmark, a woman’s name that might or might not have existed, a symbol of how history preserves some truths while erasing others.

The ink dried on his thesis as it had once dried on Sara’s marriage contracts and court documents. Another attempt to capture truth in writing, another layer added to the palimpsest of history. Outside his window, Dutch merchants still calculated profits from distant territories, the machinery of empire grinding on with mechanical indifference to individual stories.

But stories persist, even when their details blur and their meanings shift. In the name Eve Leary, in the records of Sara Thibou’s battles, in the contradiction between Joseph’s enlightenment philosophy and his family’s colonial wealth, the past continued to trouble the present, asking questions that each generation must answer anew: How do we reconcile who we are with where we came from? What do we owe to those whose suffering built our comfort? And in the end, what remains of us but the names we leave behind, echoing through history like Huguenot hymns in a darkened cellar, carrying meanings their singers never intended?

Here is a comprehensive list of the sources:

Archival Sources

•

National Archives / Archives South Holland: This archive is frequently cited as the location for digital duplicates of local administrative archives and notarial deeds from Essequibo, Demerara, and Berbice, collectively known as the ‘Dutch Series’. It also holds archives of the Tweede West-Indische Compagnie (WIC), the Society of Berbice, the Directie ad Interim and Raad der Koloniën, the Raad der Amerikaanse Bezittingen en Etablissementen, the Sociëteit van Suriname, and the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC). Specific inventory numbers and date ranges within these archives are also mentioned.

•

Amsterdam City Archives (ACA): This archive is mentioned as revealing information about financial flows. Specifically cited are the Archive of the Notaries at Amsterdam, 1578-1915 (including minutes by Hermanus van Heel and specific inventory numbers), and the Archief van de Firma Ketwich & Voomberg en Wed. W. Borski (Ketwich) (including specific inventory numbers).

•

National Archives of Guyana: Primary records from this archive were used in one study, accessible via digital copies at the Netherlands National Archives. It is also the location where the digital duplicates of the Dutch Series administrative archives and notarial deeds are held.

•

National Archives of the Netherlands (NL-HaNA): This is the location of archives such as the Archief Staten-Generaal, Tweede West-Indische Compagnie, Verspreide West-Indische stukken, and Admiraliteitscolleges / Paulus-Olivier. Specific inventory numbers are mentioned. It also hosts digital copies of records from the National Archives of Guyana (NA-NL 1.05.21 Dutch Series).

•

The National Archives (TNA), Kew, UK: Referred to as a location for related records in one study. It holds parts of the WIC archives, as well as Colonial Office (CO) archives (including volumes CO 10, CO 33, CO 76, CO 106, CO 111, CO 116 [Dutch Association Papers – DAP], and CO 243), Board of Trade (BT) records, and CUST records. Specific inventory numbers and volume ranges are detailed. It is also referred to as NA-UK and PRO.

•

Utrechts Archief (UA), Utrecht: Mentioned as holding notary records, including records from Notarissen in de Stad Utrecht 1560–1905 with specific inventory numbers.

•

Zeeuws Archief (ZA), Middleburgh: Mentioned as holding records for the Middelburgse Commercie Compagnie, including a specific inventory number.

•

United East India Company (VOC) archives: Explicitly mentioned as a source base, with parts located at the National Archives / Archives South Holland (archive number 1.04.02) including records from the Gentlemen Seventeen and Amsterdam Chamber, and Chamber Zeeland with specific inventory numbers.

•

Library of Congress: Mentioned for its map collections and for reproducing Transatlantic Sketches.

•

Geological Survey (Washington): Mentioned for its map collections.

•

Department of State (Washington): Mentioned for its map collections.

•

Lenox Library (New York): Mentioned for its map collections.

•

Harvard College (Cambridge, Mass.): Mentioned for its map collections.

•

Public Library and AtheniEum (Boston): Mentioned for its map collections.

•

U. S. G. S. Library: Mentioned as holding map collections.

•

British Colonial Office (CO) archives: Mentioned as holding parts of the WIC archive after the takeover.

•

British Archives: Mentioned as holding correspondence of various merchants.

•

North American Archives: Mentioned as holding correspondence of various merchants.

•

IISH, Collectie P. A. Brugmans: Mentioned with a specific archive and inventory number.

•

New-York Historical Society (NYHS): Mentioned as the location for the Theodore Barrell Letter book.

•

New York Public Library (NYPL), New York: Mentioned as the location for the Theodore Barrell Letter book.

•

Columbia Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML), New York: Mentioned as the location for the Barrell Family Papers.

•

Liverpool Record Office (LRO), Liverpool: Mentioned as the location for Parker Family Papers.

•

National Records of Scotland (NRS), Edinburgh: Mentioned as the location for records including correspondence of Peter Fairbairn, day book and ledger of Prospect Estate, and letter book of Thomas Cuming.

•

British Public Record Office (PRO): Mentioned as having important holdings, although less extensive than Colindale. (Also noted as an abbreviation for TNA).

•

University of Florida Library: Mentioned for its microfilm collection of British Caribbean colonial newspapers.

•

National Archives of Trinidad and Tobago: Mentioned as having holdings of newspapers.

•

Guyana National Archives: Mentioned as a source of primary records for a study.

•

United Kingdom National Archives: Mentioned as holding related records used in a study.

•

University of Guyana (UG): Listed as an abbreviation for a source, potentially archival holdings.

Published and Other Sources

•

“ArchaeologyandAnthropology_Vol25-compress.pdf”: Source document.

•

“Bermingham 2.txt”: Source document.

•

“Bermingham.txt”: Source document.

•

“Bogman Transcript.txt”: Source document.

•

“Coffij (1).txt”: Source document.

•

“Cornell_University_Library_digitization_(IA_cu31924021461409).pdf”: Source document.

•

“Early Demerara (1).txt”: Source document.

•

“Eve Leary.txt”: Source document.

•

“Fort William (1).txt”: Source document.

•

“History_of_British_Guiana_from_the_Year.pdf”: Source document.

•

“Ive Leary Familiy.txt”: Source document.

•

“Joseph Bourda (1).txt”: Source document.

•

“Joseph Matthews.txt”: Source document.

•

“Lesten leary.txt”: Source document.

•

“MH Lesten.txt”: Source document.

•

“Paadevoort.txt”: Source document.

•

“Quamina (2).txt”: Source document.

•

“Sara Thibou.txt”: Source document.

•

“Storm_van’s_Gravesande;the_rise_of_British_Guiana(IA_riseofbritishguiana01stor) (1).pdf”: Source document.

•

“The French.txt”: Source document.

•

“Thibou Family and slaves.txt”: Source document.

•

“Thomas Cuming (1).txt”: Source document.

•

“Transcription Leary 1777.txt”: Source document.

•

“Transcripts.txt”: Source document.

•

“Volume_66_Number_1and_2_1992.pdf”: Source document.

•

“dokumen.pub_borderless-empire-dutch-guiana-in-the-atlantic-world-1750-1800-9780820356082.pdf”: Source document, referred to as a book.

•

“koulen_proefschrift_pdf_-_6784f5b6c7a9e.pdf”: Source document, discussed as a study/thesis.

•

“riseofbritishguiana01stor.pdf”: Source document.

•

“slaves.txt”: Source document.

•

Authors and their works/contributions:

◦

Aa, P. v:iu <ler. Naaukeurige versaraelinK, etc., 28 vols., 12°, Leyden, 1707, vol. 21.

◦

Alexander, Captain James. E. Transatlantic Sketches, comprising visits to the most interesting scenes in North and South America, and the West Indies. 2 Vols. Philadelphia: Key and Biddle, 1833.

◦

Alexiades, Miguel N. Mobility and Migration in Indigenous Amazonia: Contemporary Ethnoecological Perspectives. Studies in Environmental Anthropology and Ethnobiology Vol.11. University of Kent: Berghahn Books, 2009.

◦

Balai, L. Het slavenschip Leusden: slavenschepen en de West Indische Compagnie, 1720-1738. Zutphen-NL; Walburg Pers, 2011.

◦

Bancroft, E. An essay on the natural history of Guiana, in South America… London-UK; Becket & De Hondt, 1769.

◦

Bailyn, B. Soundings in Atlantic History: Latent Structures and Intellectual Currents, 1500-1830. Cambridge-MT; Harvard University Press, 2011. (Also appears in Stern and Wennerlind (eds)).

◦

Benjamin, Anna.

◦

Benton, Lauren A. Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

◦

Bilby, Kenneth M. (Author of book review).

◦

Blome, Eichard (Illustrator/publisher of Sanson’s map).

◦

Brathwaite, Doris Monica. A descriptive and chronological bibliography (1950-1982) of Edward Kamau Brathwaite. London: New Beacon Books, 1988.

◦

Brown and Sawkins. Reports on the Geology of Brit. Guiana. 8°, London, 1875. (Also referred to for a geological map).

◦

Carrocera, Revd. Padre Buenaventura de.

◦

Codazzi (Venezuelan geographer and mapmaker).

◦

Crawford, N. ‘‘In the wreck of a master’s fortune’: slave provisioning and planter debt in the British Caribbean.’ Slavery & Abolition, 37 (2), 353–374, 2016.

◦

Cruz Cano (Mapmaker).

◦

Cruz, M., Hulsman, L., & Oliviera, R., de. A brief political history of the Guianas: from Tordesillas to Vienna. Boa Vista-BR; Editora da Universidade Federal de Roraima (UFRR), 2014.

◦

Curtin, P. ‘The British sugar duties and West Indian prosperity.’ The Journal of Economic History, 14, (2) 157-, 1954.

◦

Dance, Daryl Cumber. Fifty Caribbean writers: a bio-bibliographical critical sourcebook. Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 1986.

◦

De Smidt, Lee and Van Dapperen. Guyana Ordinance Book, Essequibo and Demerara.

◦

De Vries, David Pietersz. Journal of a voyage (performed in 1654, published in 1655).

◦

Duff, Revd. Robert.

◦

Farage, Nadia.

◦

Fowlie-Flores (Author of a bibliography).

◦

Genovese, Eugene D. From Rebellion to Revolution: Afro-American Slave Revolts in the Making of the Modern World. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979.

◦

Gould, Eliga H. “Entangled Histories, Entangled Worlds: The English-Speak-ing Atlantic as a Spanish Periphery.” American Historical Review 112, no. 3 (2007).

◦

Grafe, Regina. Distant Tyranny: Markets, Power, and Backwardness in Spain, 1650–1800. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

◦

Grafe, Regina. “On the Spatial Nature of Institutions and the Institutional Nature of Personal Networks in the Spanish Atlantic.” Culture & History Digital Jour-nal 3, no. 1 (2014).

◦

Handler, Jerome S. Searching for a slave cemetery in Barbados, West Indies: a bioarcheological and ethnohistorical investigation. Carbondale IL: Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, 1989. (With Michael D. Conner and Keith P. Jacobi).

◦

Harris & de Villiers. See Harris, C. & De Villiers, J..

◦

Harris, C. & De Villiers, J. Storm van ’s Gravesande. The rise of British Guiana. Compiled from his Dispatches. London-UK; The Hakluyt Society, 1911. (Parts of their work are also cited).

◦

Hart, M., ‘t. ‘Corporate governance.’ In De wisselbank: van stadsbank tot bank van de wereld. Nieuwkerk, M. van, & Kroeze, C., 2009.

◦

Hart, M., ’t., Jonker, J., & Zanden, J., van. A financial history of the Netherlands. Cambridge-MA; CUP, 1997.

◦

Hartmann, A. Repertorium op de literatuur betreffende de Nederlandsche koloniën, voor zoover zij verspreid is in tijdschriften en mengelwerken, 1895.

◦

Hebert (Mapmaker).

◦

Hemming, John.

◦

Hilhouse. Jour. Royal Geogr. Soc, Vol. IV.

◦

Hoonhout, Bram and Thomas Mareite. “Freedom at the Fringes? Slave Flight and Empire-Building in the Early Modern Spanish Borderlands of Essequibo–Ven-ezuela and Louisiana–Texas.” Slavery & Abolition, 2018.

◦

Horan, Joseph. “The Colonial Famine Plot: Slavery, Free Trade, and Empire in the French Atlantic, 1763–1791.” International Review of Social History, Sup-plement S18, 2010.

◦

Horstman. Horstman’s Journal.

◦

Hovy, Johannes. Het voorstel van 1751 tot instelling van een beperkt vrijhavens-telsel in de Republiek (propositie tot een gelimiteerd port-franco). Groningen: J. B. Wolters, 1966.

◦

Hubbard, Vincent K. A History of St Kitts: The Sweet Trade. Oxford: Macmillan, 2002.

◦

Hulsman, L. A. H. C. “Nederlands Amazonia: Handel met indianen tussen 1580 en 1680.” PhD diss., University of Amsterdam, 2009. (Also listed with Cruz, M., & Oliviera, R., de.).

◦

Humboldt, Alexander von. Personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regions of America, during the years 1799-1804. New York-NY; Cosimo Classics, 2009. (References to his work and observations are cited).

◦

Im Thurn. Among the Indians of Guiana.

◦

Ingram, K. Manuscripts relating to Commonwealth Caribbean countries in US and Canadian repositories. St., 1975.

◦

Kars, M. ‘Dodging rebellion: politics and gender in the Berbice slave uprising of 1763.’ The American Historical Review, 121 (1) 39–69, 2016.

◦

KITLV. ‘Memorie van den Amerikaanschen raad over de Hollandsche bezittingen in West-Indië in Juli 1806.’ NWIG, 4 (1) 387–398. Leiden-NL; KITLV, 1923.

◦

Klooster. Dutch Moment.

◦

Koulen, Ingrid and Gert Oostindie. The Netherlands Antilles and Aruba: a research guide. Dordrecht: Foris, 1987.

◦

Koulen, Paul. “Slavenhouders en geldschieters,”. (Also transcribed a list of mortgages).

◦

Krichtal, A. Liverpool and the raw cotton trade: a study of the port and its merchant community, 1770–1815. MA-thesis, Victoria University, Wellington-NZ, 2013.

◦

La Condamine.

◦

Laet, J., de. Nieuwe wereldt ofte beschrijvinghe van West-Indien… Leiden-NL; Elzevier, 1625.

◦

Lagemans, E. Recueil des traités et conventions conclus par le Royaume des Pays-Bas avec les puissances étrangè-, 1858.

◦

Laurence, K. A selection of papers presented at the 12th Conference of the Association of Caribbean Historians: 1980. St. Augustine-TT; Association of Caribbean Historians, 1985.

◦

Lawrence-Archer, J. Monumental inscriptions of the British West Indies from the earliest date:… London-UK; Chatto & Windus, 1875.

◦

Lean, J. The secret lives of slaves: Berbice, 1819 to 1827. PhD-thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch-NZ, 2002.

◦

Lee, R. ‘Roman-Dutch law in British Guiana.’ Journal of the Society of comparative legislation, 14 (1) 11–23, 1914.

◦

Lent, John (Author of previous lists/books on media).

◦

Martfnez, Julio A. Dictionary of twentieth-century Cuban literature. Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 1990.

◦

Menezes, Sister Mary-Noel.

◦

Nelson, Carlos (Compiler of a bibliography).

◦

Netscher, P. Geschiedenis, 1888. (Also cited for precis of de Vries’ journal and History of the Colonies).

◦

Pactor, Howard S. Colonial British Caribbean newspapers: a bibliography and directory. Westport CT: Greenwood, 1990.

◦

Petley, C. ‘West Indian slavery and British abolition, 1783–1807, by David Beck Ryden.’ EHR, CXXVI (519) 468–470. Oxford-UK; OUP, 2011.

◦

Piketty, T. Capital and ideology. Cambridge-MA, Harvard University Press, 2020.

◦

Piketty, T. A brief history of equality. Cambridge-MA, Harvard University Press, 2022.

◦

Pinckard, G. Notes on the West Indies:… (I, II, and III). London-UK; Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1806.

◦

Price (Author reviewed).

◦

Ralegh, Walter. Discoverie of Guiana. 1596. (Also referenced in text on maps).

◦

Rapport Grovestins and Boeij.

◦

Roegiers, J. ‘Revolution in the North and South, 1780-1830.’ In History of the Low Countries. Blom, J., New York-NY; Berghahn Books, 2006.

◦

Roessingh, M. Guide to the sources in the Netherlands for the history of Latin America. The Hague-NL; Government Publishing Office, 1968.

◦

Rogge, C., & Allart, J. Geschiedenis der staatsregeling, voor het Bataafsche volk. Amsterdam-NL; Allart, 1799.

◦

Roitman, J. ‘Creating confusion in the colonies: Jews, citizenship, and the Dutch and British Atlantics.’ Itinerario, 36 (2), 55–90. Leiden-NL; Leiden University Institute for History, 2012.

◦

Rose, J. ‘British West India commerce as a factor in the Napoleonic war.’ Cambridge Historical Journal, 3, 1929.

◦

Russell-Wood, A. J. R. “Center and Peripheries in the Luso-Brazilian World, 1500–1808.” In Negotiated Empires. Daniels and Kennedy, 105–42.

◦

Ryden, David. West Indian Slavery and British Abolition, 1783–1807. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

◦

Salvucci, Linda K. “Supply, Demand, and the Making of a Market: Philadelphia and Havana at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century.” In Atlantic Port Cities. Knight and Liss, 40–57.

◦

Sanson, Monsieur (Geographer and mapmaker).

◦

Schaffer, Simon, Lissa Roberts, Kapil Raj, and James Delbourgo. “Introduction.” In The Brokered World. Schaffer, Roberts, Raj, and Delbourgo, ix–xxxviii. (Also referred to for another essay in this volume).

◦

Schneider, Elizabeth Ann (Author of book review).

◦

Schomburgk, Richard. Reisen in Britisch Guiana.

◦

Schomburgk, Robert. Reports. (Also mentioned for his notes to Raleigh’s Guiana and as author of the Great colonial map).

◦

Sepp, D. Repertorium op de literatuur betreffende de Nederlandsche koloniën, voor zoover zij verspreid is in tijdschriften en mengelwerken. The Hague-NL, Nijhoff, 1935.

◦

Sewell, W. The ordeal of free labor in the British West Indies. New York-NY, Harper & Brothers, 1861.

◦

Sheridan, R. ‘The commercial and financial organization of the British slave trade, 1750–1807’. EHR 11 (2) 249-263. Glasgow-UK; W-EHS, 1958.

◦

Sheridan, R. ‘The British credit crisis of 1772 and the American colonies.’ The Journal of Economic History, 20(2), 1960.

◦

Staehelin, F. (Publisher of ThePilgerhut diary).

◦

Stanford (Publisher of the Great colonial map).

◦

Stern, Philip J. and Carl Wennerlind (eds). Soundings in Atlantic History: Latent Structures and Intellectual Currents, 1500-1830. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

◦

Stoner, K. Lynn. Latinas of the Americas: a source book. New York: Gar-land Publishing, 1989.

◦

Strickland, Father. Documents and Maps on the Boundary Question. (Also referred to for lists and maps).

◦

Sturm-Lind, Lisa. Actors of Globalization: New York Merchants in Global Trade, 1784–1812. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

◦

Surville (Mapmaker).

◦

Sweet, David.

◦

Temin, Peter, and Hans-Joachim Voth. “Credit Rationing and Crowding Out during the Industrial Revolution: Evidence from Hoare’s Bank, 1702–1862.” Explorations in Economic History 42, no. 3 (2005).

◦

Temin, Peter, and Hans-Joachim Voth. “Hoare’s Bank in the Eighteenth Century.” In The Birth of Modern Europe: Culture and Economy, 1400–1800. Edited by Laura Cruz and Joel Mokyr, 81–108. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

◦

Thompson, Mark L. The Contest for the Delaware Valley: Allegiance, Identity, and Empire in the Seventeenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013.

◦

Villiers. See Harris, C. & De Villiers, J. and Villiers, Storm van ‘s Gravesande.

◦

Villiers, Storm van ‘s Gravesande.

◦

Varenius. Cosmography and geography, 3d ed. fol. London, 1693.

◦

Webber and Christiani. Hand-book of British Guiana.

◦

Whitaker, James.

◦

Whitehead, Professor Neil.

•

Reports, Journals, Maps, and Document Types (where noted as sources):

◦

Annates de Voyages (Paris, 1857), Vol. 74.

◦

Atlas of the Commission, map 73 (Capuchin map of 1771).

◦

Blue Book, Venezuela (1896). (Full title: Documents and correspondence relating to the question of boundary between British Guiana and Venezuela…).

◦

Blue Book “Venezuela, No. 1”.

◦

Blue Book “Venezuela, No. 3”.

◦

Documents and Maps on the Boundary Question (by Father Strickland).

◦

Documentos para la Itistoria . . . del Libertador, I.

◦

Doimmentos (described in a note after).

◦

EHR (Journal).

◦

Explorations in Economic History (Journal).

◦

Geological map of Brown and Sawkins.

◦

Great colonial map of British Guiana (by Schomburgk/Stanford, 1875).

◦

Interrogations (manuscript pages).

◦

International Review of Social History (Journal).

◦

Itinerario (Journal).

◦

Journal of the Society of comparative legislation.

◦

Jour. Royal Geogr. Soc (Journal).

◦

Minutes of Police of the Governor-General and Councils of Essequibo and Demerary. Copy.

◦

Minute Book (original and copy).

◦

Mortgage deeds registered in Guyana.

◦

Nederlandsche Leeuw (Ned. Leeuw) (Journal).

◦

Nieuwe West Indische Gids (NWIG) (Journal).

◦

Parliamentary Papers, published in 1896.

◦

Power of Attorney dated July 12th, 1735.

◦

Punch (Publication).

◦

Rapport Grovestins and Boeij.

◦

Register van plakkaten, bekendmakingen, instructies, reglementen etc..

◦

Resolutie Boek, Kamer Zeeland.

◦

Spanish sources (used in translation in boundary dispute books).

◦

Testamenten.

◦

ThePilgerhut diary.

◦

The American Historical Review (Journal).

◦

The Journal of Economic History (Journal).

◦

Timehri (The Journal of the Royal Agricultural and Commercial Society of British Guiana).

◦

Tijdschrift Surinamistiek en Caraïbisch gebied (OSO) (Journal).

◦

Trade statistics from the British Caribbean.

◦

Unpublished theses and dissertations.

◦

Ven. Arb. Brit. App. i..

◦

Venezuelan “Documents,” I.

◦

Venezuelan “Documents,” III.

◦

Written contract.

This list compiles all the sources mentioned within the provided excerpts, including archives, specific archival holdings, published books, articles, journals, reports, and other documents.

Discover more from Random Ramblings by Robert Steers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.